“In this, we see the long arc of our culture care vision: that art, when faithful to the soul and attentive to the world, becomes not a mirror but a common table. A place where we gather, break silence, and become aware again of what is sacred.”

- Makoto Fujimura

Heading image: Sakai Hōitsu (Japanese, 1761 – 1828), Blossoming Cherry Trees (left screen, overall), c. 1805., pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, and gold leaf on paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain.

A Note from IAMCultureCare

This month, Mako Fujimura reflects below on a recent conversation with James Jordan, the grammy-winning conductor and pedagogue at Westminster Choir College, about the transformative power of presence in music.

Presence is difficult to put into words, but those who have felt it know exactly what Jordan is talking about — the collective, improvisatory play between a composer and musician, between individual performers in an ensemble, between the ensemble and the audience. It’s the difference between a live performance and a recording, which may “sound” the same in theory, but which are entirely different experiences. And that’s not just true of performance arts (music, dance, theater, stand-up comedy, spoken word); there is a similar interplay and dichotomy for a painting viewed in person versus a digital reproduction, a poem written versus spoken aloud. Art — and life — have to be lived, presenced, to be fully known.

I had a rare (for me) opportunity to experience the power of presence as an audience member rather than performer this past weekend. The setting and program was thus: a university rehearsal hall on a sleepy Sunday afternoon, the rain gently beating against the window, and seven chamber ensembles — undergraduate and graduate winners of a recent competition — slated to perform.

At the best of times, university-level performances awkwardly straddle the line between professional concert and charity case: some audience members are there as “patrons of the arts.” Others are moral support for their loved ones. Neither group knows in advance whether the concert will be extraordinarily beautiful or extraordinarily painful; often it is both.

In our case, we were on edge from the beginning. More than any “mistake” (such as a missed or out-of-tune note, a wrong entrance), an obviously fearful performer can quickly break the unspoken contract of trust with the audience. The first two groups filled us with just such a nervous anticipation, but we were finally settling down into a confident performance of the Rachmaninoff Cello Sonata when the unthinkable happened: midway through the piece the lights suddenly went out. The room was plunged into semi-darkness.

Remarkably, the performers kept playing. And amidst our discomfort, uncertainty, anxiety, a curious thing happened: we committed ourselves to trusting that the musicians would be okay without light, and when we did so the music and communal experience opened up in a new way. We were fully present, the music fully alive, and the invisible barrier between performer and audience broke down in the absence of the harsh spotlights. There was an intimate immediacy to it all. We were one, consummate whole taking part in this thing we call music. The performance — I hesitate to call it that now, implying as it does a definable act rather than a shared presence — was exquisite, and the final, resonant silence felt an eternity in the half-light and half-sound of the last chord.

This is a slightly humorous example of the power of presence in art, but it is not atypical. We encounter a myriad of similar experiences throughout our lives in museums, concert halls, street corners, gardens, shared meals, conversations. But what do we do with these life-changing moments? Where do we go from there? In other words, how do we practice presence after the silence is broken?

An encounter with the presence of supreme beauty places an unspoken and uncomfortable duty upon us. Applause — our default response — is often a subconscious attempt to immediately placate the call toward transformation. Rather than bear beauty’s haunting gaze for another moment, we turn from its lingering presence not to the source but to the conduit, and so we applaud the artist. (That is not to say that celebrating an artist’s work is not a good and necessary thing, but rather that it can at the same time be an excuse to abdicate further responsibility.) And so I wonder what might happen if we could instead carry that breathless stillness before the applause with us into the world. I suspect our frenetic, combative culture would be transformed; I know we would.

That’s all from me for now. I’m off to perform several concerts this weekend—sacred music of Orlando Gibbons, Bernstein’s infamous Overture to Candide, some Bizet, and Sibelius’s First Symphony — and looking forward to experiencing more of these liminal moments of presence that make this art so worthwhile. I hope you will join me in cultivating such moments in your corners of Culture Care this month.

Jacob Beaird, Editor

A Note from Mako Fujimura, Founder of IAMCultureCare

“To Allow, To Behold, To Sing”

After a recent conversation with Maestro James Jordan at All Saints Church Forum on Faith and Life, I was left with awe in the mode of a deeper listening we experienced together.

The choir, as Jordan reminds us, is not merely an artistic ensemble. It is a fragile ecology of persons — of bodies, stories, resistances, and hopes — brought into “honest” harmony not by force, but by attention of care. “Allowing” is the rare discipline of relinquishing control so that something truer than the self might emerge in the community. To conduct, in his vision, is not to command but to “listen aloud” with the body, to create an atmosphere where others may be given permission to become fully human. “I try to cause something to happen,” he says, not by dominating the music, but by being present enough to draw it out.

This is Culture Care. The act of cultivating conditions for flourishing, for mystery, for a common song in a fractured time. We heard, in Jordan’s reflections, that what endures in the memories of his students is not technique but tenderness — not perfection, but presence. The mark of a life lived toward others, conducted in the spirit of hospitality. In this, we see the long arc of our culture care vision: that art, when faithful to the soul and attentive to the world, becomes not a mirror but a common table. A place where we gather, break silence, and become aware again of what is sacred.

What if this is our work now in this fractured age? Not merely to perform but to “become” instruments of peace, of breath shared. What if to care for culture is to apprentice ourselves to the miracle of communal song — to feel the chemistry and trust between strangers who agree to sing the same note, at the same time, for no other reason than joy?

Jordan’s pedagogy of breath and awareness speaks not only to musicians, but to anyone resisting the flattening and increasingly violent clamor of our age. In a world addicted to urgency, beholding is rebellion. In a culture commodifying even the sacred, honesty in art — honesty in “presence” — is a slow-burning revolution.

Culture Care, then, is not merely aesthetic. It is liturgical. It is the prayer of the human gathered in communion with others, shaped by attention, humility, and love. It is what allows music to become more than sound — it becomes a shelter for many.

As we move toward an uncertain future, let us take to heart the wisdom of these teachers: To listen for what is not on the page. To dream with others. To make space where others can grow larger, even if it means becoming smaller ourselves. To risk the vulnerable art of being human — together.

Yours for Culture Care,

Mako Fujimura

Guest Reflection: Karen Lacy

When I was in my mid-20s, I took a trip to Europe with my best friend. We saved up for two years and bought a Euro-rail pass that allowed us to hop on and off the train, exploring as many countries in 2.5 weeks that we could (with a limited budget). Our last stop on this special trip was Amsterdam, where I discovered my love for Vincent Van Gogh after spending an afternoon at the Van Gogh Museum. My friend and I soaked up all we could about this artist whose main works I knew—The Starry Night, Sunflowers, his many self-portraits (there’s a whole floor of them at the museum)—but whose vast repertory of other works I did not. Wandering around the museum floors, I discovered one painting that grabbed my attention in a new way: The Cottage.

Vincent van Gogh (1853 — 1890), The Cottage, 1885, oil on canvas, 65.7 cm x 79.3 cm. Image courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), Public Domain.

Painted in 1885, just five years before he died, this work was different, not like his more familiar pieces bursting and swirling with color. Something about it stopped me, compelling me to take a closer look.

From an initial sense of overall darkness and dim shades of earth tones, I began to see more: the sun setting behind the dark clouds, still showing a streak of light, the contours of the ground strewn with small rocks, the outline of the bare trees against the grey clouds, the lines and patches on the thatched roof, and then…one tiny speck of orange breaking through a window, suggesting a fire inside. One small light became the focal point of it all, grabbing my eye, drawing me in. Amidst the darkness, light broke through and the painting opened up for me in a whole new way. No longer did I see a dark, barren landscape, but rather a welcoming place, a home, more than just a small cottage on a plain. A single, orange flame revealed layers and depths of vision throughout the canvas.

As a dance educator and staff member of Embers International, I recently had the opportunity to teach dance to children who live in a slum in Southeast Asia. One boy lived with his parents on the second floor of a public toilet; another girl’s mother had been wrongfully imprisoned; almost all of the children slept in places that we in the Western world wouldn’t consider livable, as dark and rundown as the exterior of a small cottage.

Yet, the joy that was evident in their faces and bodies as they moved to the music was like seeing the speck of light breaking through the window in Van Gogh’s painting. In the midst of a place covered with dirt and dust, smog and decay, poverty and life challenges beyond fathoming, the light broke through. For a few brief moments, the children were transported from the physical barrenness of their lives into the brightness of imagination through dance, moving to music from The Nutcracker and the glorious melodies of a hymn about the beauty of the earth. Like the faint orange glow of Van Gogh’s fire inside a cottage at twilight, these children felt welcomed in the warmth of moving their bodies to beautiful music.

I hope I always live in a way that sees like Van Gogh and shines like children rising above their circumstances in a dark place. All it takes is one small flame.

Karen Lacy is a Philadelphia-based dancer, dance educator, and advocate for victims of injustice through her work at Embers International

Susie Ibarra Wins Pulitzer Prize

Long-time Culture Care advocate and musician Susie Ibarra has just won the Pulitzer Prize in Music for her 2024 work Sky Islands! Composed for her eight-piece ensemble, the piece is a musical tribute to our rich and fragile ecosystems inspired by the distinct rainforest habitats of Luzon, Philippines, and it reflects the musical traditions and style of the area.

As a percussionist, Susie has frequently collaborated with Mako Fujimura for his live paintings as well as their collective Walking on Water project—Mako’s painting series accompanied by Susie’s compositions in an album of the same title. A few years ago Mako interviewed Susie on the Culture Care podcast about their Walking on Water work which is “an elegy to the climate change crisis, as well as an homage to human resilience of hope in dire circumstances.” It’s worth a listen.

We at IAMCultureCare in wish Susie congratulations on this milestone, and Mako writes that “We are grateful for Susie’s courage and perseverance to continue to make art that speaks into our souls in our fractured time.”

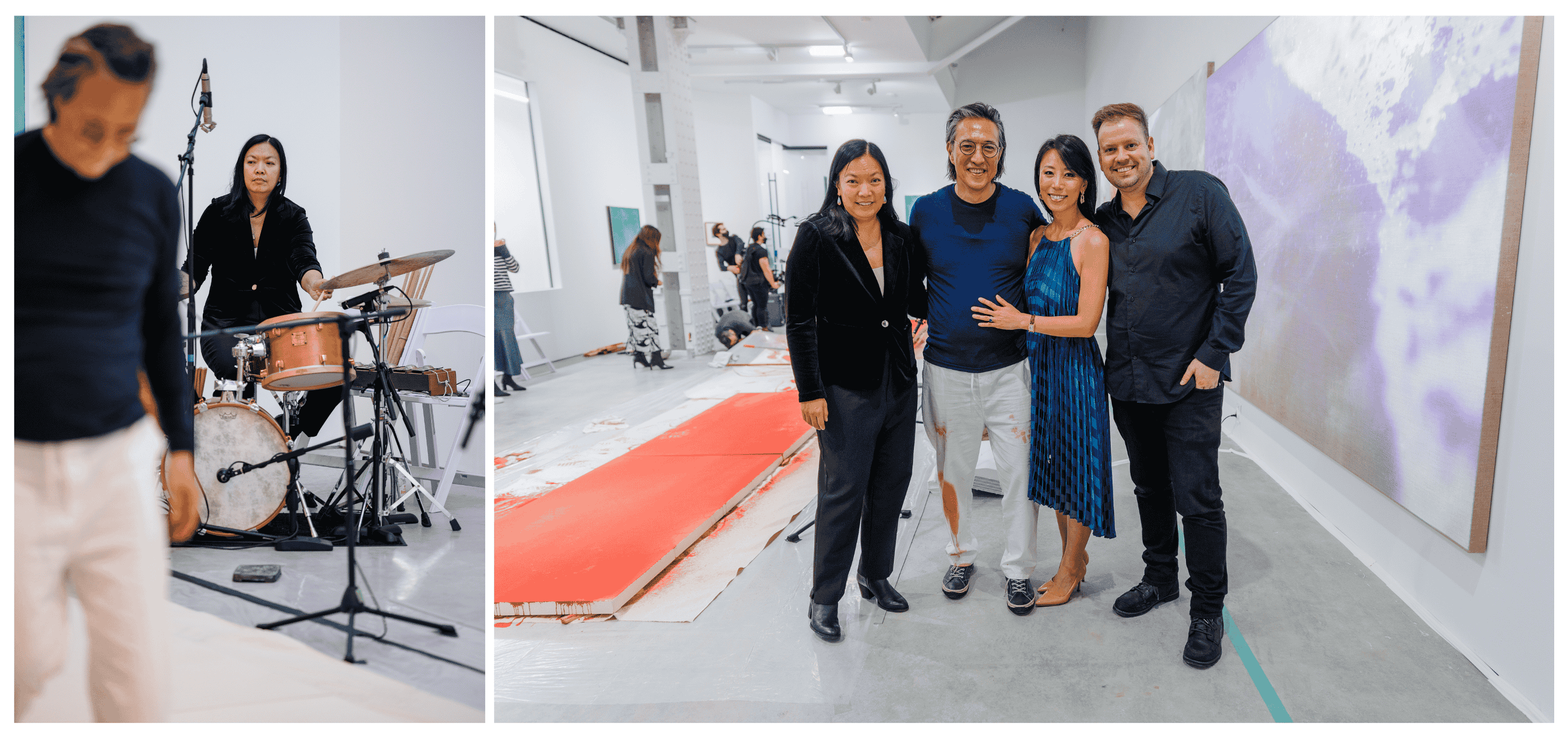

Makoto Fujimura painting live with Susie Ibarra on percussion in Chelsea, NYC in 2021 (left). Also pictured (far right) is Stephen Proctor, who we featured in the September, 2024 newsletter. Stephen’s drone videography was projected over Mako’s Sea Beyond triptych during this live performance/painting.

Culture Care Events & Announcements

- Transfiguration Exhibit—Philadelphia, PA, Now-June 1. Mako Fujimura’s monumentaltriptych is exhibited at the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts.

- Gordon College 2025 Commencement Address—Boston, MA, May 17. Mako Fujimura to deliver the Gordon College 2025 commencement address on “Beholding for Generations: The Art of Becoming”. Fujimura will receive an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts degree from the school during the commencement ceremony.

- STAY TUNED: Gordon College Exhibition—Boston, MA, August 27-October 15. Mako Fujimura and Bruce Herman to exhibit their original works from the QU4RTETS project alongside newer works by Fujimura in a special exhibit in Gordon’s Barrington Center for the Arts. Additional details TBA.

- Makoto Fujimura: Art Is: A Journey Into the Light is published October 21. Mako’s next book with Yale University Press will be available this fall wherever books are sold (pre-order now from any of the retailers linked here!). Art Is takes readers along on Mako’s meandering journey as an artist. We witness him making his “process-driven slow art” — using pulverized minerals, gold, or pigments made from oyster shell — as he considers the plants and wildlife on the land where he lives. Bringing together the author’s written reflections and over 70 of his paintings, drawings, and photographs in full color, Art Is invites us to see the world in prismatic and diverse lights, helping us navigate the fractured, divisive times we live in. Pre-order is available now.

Do you have a news item or upcoming culture care event? Consider sharing it with us for a possible feature here in the newsletter! Email jacob@internationalartsmovement.org.

Web Links

- Mako Fujimura and Julia Hendrickson’s latest Belonging Conversation.

- On the (un)worthiness of comments, internet or otherwise, from Richard Gibson for The Hedgehog Review.

- Matthew Milliner interviews Jonathan Anderson in Comment.

- The songs that made the hit pop charts of the 1600’s, from the Folger Shakespeare Library podcast.

- The MET Museum’s Sargent and Paris exhibit in a virtual tour.

- The Art Institute of Chicago cleans a Cassatt.

- The New Yorker profiles a cimbalom player.

- The intricate travel notebooks of José Naranja.

- New music recs: Grammy and Pulitzer-winner Caroline Shaw joins Danni Lee Parpan as the cinematic electric-pop duo Ringdown with a debut album; I Fagiolini’s historical reconstruction of a choral Vespers service in 1612 Italy (with notes).

IAMCultureCare is a registered 501c(3) non-profit organization that relies on your support to continue our Culture Care efforts of amending the soil of culture as an antidote to toxic culture wars. This newsletter and our other programming do that effectively, and we welcome gifts of any size to continue these efforts. You can donate here or get in touch with us about corporate sponsorship!

All content in this newsletter belongs to the respective creators, as noted, and is used with permission. If you would like to submit something for consideration in a future newsletter issue, you may do so by filling out this form or by emailing jacob@internationalartsmovement.org.