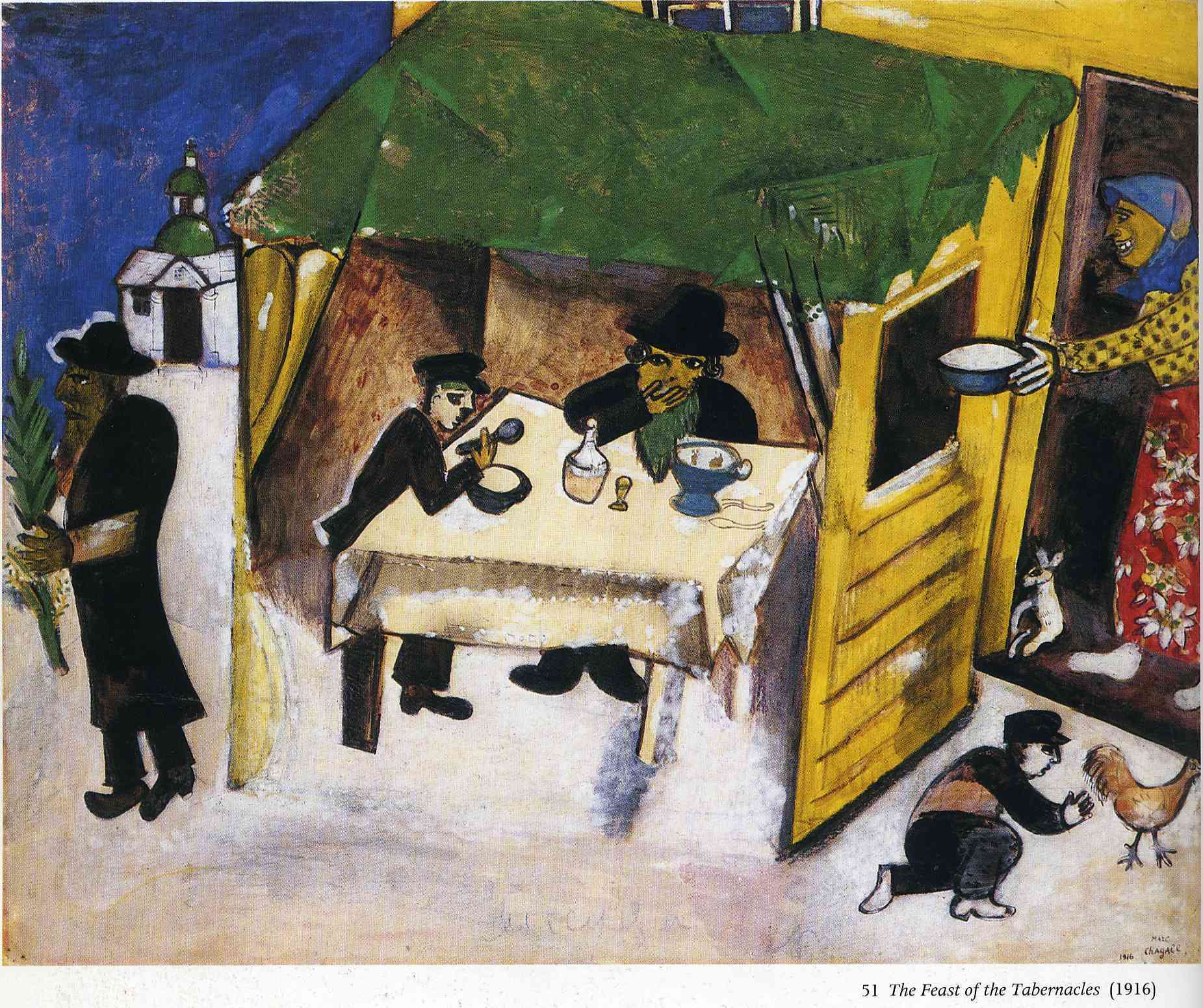

Marc Chagall, The Feast of the Tabernacles, 1916, gouache, 33 x 41 cm, https://www.wikiart.org/en/marc-chagall/the-feast-of-the-tabernacles-1916. Public Domain.

A Note from IAMCultureCare

Many thanks to those of you who filled out our recent survey! If you missed the email link, you can still do that here. Tell us about how you have been doing culture care and let us know your interest in contributing to this newsletter in the future. We would love to hear from you as we seek to expand our community and amplify the crucial work that you are already doing around the world.

On that note, we are thrilled to welcome submissions of all types for consideration in future monthly editions, whether that is art, reflection/short essay, music, poetry, dance, Culture Care news updates from your corner of the world, or anything else you think might be appropriate. You can submit content for consideration or ask us any questions by emailing jacob@internationalartsmovement.org.

It is clear from your survey responses that Culture Care is more needed than ever, especially in light of recent global events. It is also clear that this movement doesn’t happen in isolation. Curated each month, we hope that our collective stories in this newsletter will be catalysts for change and serve as examples of the many (often informal) ways that Culture Care can play out in our communities.

This month, we feature one such reflection below by Academy Kintsugi (IAMCultureCare partner, now dedicated to Kintsugi Peace-Making) facilitator Troy Kirk. Troy writes about beholding brokenness in Kintsugi and life, and how the attentive act transforms the beholder and the beheld. Mako Fujimura (founder of IAMCultureCare) also reflects on the Jewish holiday of Sukkot and culture care that creates true shalom. Mako and Troy’s words inspire all of us in our efforts towards creating beauty out of brokenness.

A Note from Makoto Fujimura, Founder of IAMCultureCare

In recent days the world has watched the brutal attack by Hamas, breaching the Gaza walls and target first an Israeli music festival three miles across the Gaza border. The festival was called “Supernova Sukkot”, and was designed to overlap with the “Festival of Tabernacles” culminating in the beginning of a new year of the Jewish Calendar.

Sukkot has implicitly been at the center of my thesis of “Theology of Making”. During these holy days, Jews traditionally live in sukkōt, or booths/tabernacles. These tabernacles are reminiscent of the nomadic life of the Israelites during the Exodus, as well as the Tabernacle of Moses. For me, this festival is a reminder of two artisans named in the Exodus account: Bazalel and Oholiab. These two designed the Ark of the Covenant according to God’s strict instructions given to Moses with the Decalogue. Significantly, the Tablets of Ten Commandments were to be housed inside the Ark and placed in the Tabernacle, (and eventually in the Holy of Holies in Solomon’s glorious Temple). Bazalel and Oholiab are the first people recorded in the Bible as being “filled with the Spirit” (noting again how important artists/artisans are for The Artist, God), and their work brings attention to the heart of worship for the nomadic tribe of God’s people. Sukkot, for me, is a day to remember their act of making. Having a music festival to celebrate life as a nomadic tribe in the borderlands would be an appropriate response.

But now Sukkot will be remembered as the worst act of terrorism in the land of Israel, and the worst act of anti-Semitic terrorism since the Holocaust. The joyful Sukkot celebration will now be overshadowed by our lament and grief. Those celebrating life became the first victims of this atrocity. Such marks our world today. Military reaction by the state is not unfamiliar to me as a survivor of 9⁄11, and I expect it to dominate the news in the coming years. Yet we must remember that the Hebrew word “Shalom” is much more than the absence of violence and war. It is to see the flourishing of all people in all lands. We are not “peace-keepers” in that sense, as the fragile conditions of the Israel/Palestine or Ukraine/Russia borders were never “Shalom” in the first place. That is why we need to be Peace-Makers, creating peace through the arts amidst conflict. That is a generational calling.

I have travelled to Israel/Palestine three times, and now I fear the next trip will not be for a long time. Here are some photos, one taken in Palestinian territory near Bethlehem, with Banksy’s mural for shalom. The other is taken in Golan Heights overlooking Syria, walking and praying for the lands south of the overlook with so much imbedded meaning and history. My exhibit at Haifa’s Tikotin Museum was not far from where I stood, and certainly within missile range of the Syrian military.

May our art, like Banksy’s mural, be prayers for Shalom.

Guest Essay: To Behold

By Troy Kirk, Academy Kintsugi Facilitator

I recently had the privilege of participating in a gathering of Academy Kintsugi facilitators (partner of IAMCultureCare) for a time of training and fellowship. Filled with joy and laughter and much contemplation, this reunion of friends, both old and new, was an incredibly meaningful occasion. Led by a gifted and generous group of leaders, we deepened our appreciation for the traditions of Kintsugi and were renewed in our understanding of the foundations of culture care.

During a time of reflection at this gathering, we were invited to join Academy Kintsugi’s leaders in a period of beholding that would extend well beyond our time together. It was an invitation to apply the Kintsugi practice of beholding to the life of our community. I have been reflecting on this invitation ever since.

Beyond the technical skill and patience to mend what is broken and the artistic competence and imagination to create something new, I am convinced that the most difficult, yet perhaps most powerful, discipline of Kintsugi is what is required even before any mending or making begins. It is the call to behold the broken creation that rests before us and to do so until we begin to see its beauty. To behold requires us first to make space and time. To slow down. To be present and rooted. And in that place of stillness, to generously give our full attention – seeing with all of our senses and a contemplative vision from within.

Wrestling with why beholding is so difficult, it seems at first glance that our demanding schedules, instant gratification, and the ever-growing competition for our attention are all part of a strong current running against the discipline of beholding. But this struggle is not a new one. We are restless and self-oriented beings, relentlessly maneuvering to fill our unmet longings and often fearful of what we may encounter in that place of stillness. And Kintsugi’s call to pull back on the reins and slow down to behold a broken vessel before starting the mending process requires a relinquishment of our urge to take control and get our hands busy fixing toward productivity and completion.

But while the discipline of beholding is difficult, it is a worthy pursuit – both in Kintsugi and life in general. For as we behold, we shift our inward and downward gaze away from ourselves and toward a fellow created being and in so doing affirm the dignity and honor of the other. It is a humble gesture that conveys to this broken embodiment of beauty that it is worthy of being seen and loved. When our senses begin to comprehend the beautiful before us, we experience an inner soul-type movement. It is as if the beauty we encounter calls to beauty within us, and when we slow and pause long enough to hear it, our entire being is drawn in its direction, held in a moment of wonder, and then directed toward something deeper and more transcendent. Twentieth century Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar explained that within this appearance of the form of beauty, “the truth and goodness of the depths of reality itself are manifested and bestowed” – the form of beauty is the real presence of the depths and simultaneously points beyond itself to greater depths, and ultimately toward the invisible God (Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics (Volume I: Seeing the Form), 115 – 116). As we are carried beyond ourselves in this way, there is the hope of our ongoing formation into an embodiment of beauty.

For as we behold, we are changed. And as we are changed, we are better able to behold. In this dance, this integration loop, we may begin to understand that perhaps our biggest challenge is to recognize ourselves as broken vessels and to rest in the knowledge that even in our brokenness we hold the loving gaze of God and are seen as beautiful, by and through and because of the one true and good Broken Embodiment of Beauty. From that place of rest, we may then be freed to behold beauty in the other.

Web Links

- Generative AI and machine learning experiments continue to evolve in surprising ways. Turning aside from large language models like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, researchers are finding results from tiny language models. Creative limits are seemingly also effective for the machines — at least for writing children’s stories.

- The Foundation Louis Vuitton is hosting France’s first major Rothko retrospective since 1999, with 115 works from major collections around the world. If you’re able to get yourself to Paris this fall be sure to visit.

- Solo vocal ensemble I Fagiolini just recorded music by Orazio Benevoli (1605−72), a long-forgotten Italian Baroque composer. I Fagiolini’s music director Robert Hollingworth takes us behind-the-scenes to explore the unique process of resurrecting this elaborate music.

- A follow-up on last month’s “Culture Care Sound-bite”: a free opportunity THIS week in Chicago to hear music by William Byrd he composed in secret.

- Are you an artist looking for a meaningful way to advocate for justice, mercy, and hope for the oppressed? Learn how you can join IAMCultureCare’s partnering organization Embers International as an Artist Advocate by emailing Bianca for more information (bianca@embersinternational.org) to join Mako and others creatives in this effort.

- Thanks to all who attended the opening of Makoto Fujimura’s My Bright Abyss: Paintings and Prints exhibit in Nashville, TN. The exhibit remains open to visit on select dates through the end of March 2024.