“As artists, as makers, as cultivators of beauty, we are entrusted with the work of patient tending. The soil of our time feels eroded by anxiety and speed, but even so — perhaps especially so — our calling is to plant, to listen, to watch for signs of the invisible becoming visible.”

- Makoto Fujimura

Heading image: Giotto di Bondone (Florence, 1267 – 1337), “Saint Francis Preaching to the Birds”, predella detail from Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata, c. 1295 – 1300. Tempera and gold on panel. The Louvre, Public Domain.

A Note from IAMCultureCare

I recently came across an article comparing two streams of historic sacred music — Gregorian chant and polyphony — as representative of the divergent but complementary metaphysics of Augustine and Thomas Aquinas. There was much to be commended about the piece, but as a student of both aesthetic theology and music history I was also frustrated: not with the conclusions per se, nor with the exercise of examining art through a theological lens (much of our broader community explores intersections like these in creative and productive ways), but with the author’s assumptions about the origins of the musical works discussed.

Specifically, the article assumed a metaphysical framework as the inspiration for a work of art, such that the artwork represents an idea from its very conception. Yet this is both historically and practically inaccurate. Sure, we can read metaphysics into chant or polyphony, but these musical forms did not come about as theoretical experiments in representing theology in artistic media. Artistic expression is organic, created in community by people committed to beauty not as an idea but as concrete reality: a sunset, a particularly pleasing assonance, a melodic motive. Music — art — (at least the truly transformative stuff) is rarely just an expression of philosophical ideals, able to be boiled down into “good” vs. “bad”, “sacred” vs. “secular”, “high” vs. “low”.

In the case of these musical styles, it’s also impossible to separate sacred polyphony from secular madrigal traditions or plainchant from the singing found in secular venues of the time. In fact, perhaps the most famous tune in medieval and renaissance mass settings comes from a popular French tavern song, “L’Homme Arme” (“The Armed Man”). Or, consider Martin Luther’s chorale tunes now immortalized in J.S. Bach’s music. Most of these are not original compositions but rather popular [secular] tunes repurposed because Lutheran congregations already knew them from outside their church context. The church has always been borrowing from and sanctifying elements of the wider culture, and that should be celebrated rather than suggesting that sacred art is either historically distinct or solely metaphysically motivated.

Now, this might seem like a minor historical quibble, relevant only to classical music nerds, but it does matter for our Culture Care work. Art is by nature nuanced and intuitive. It matters that some of the most beautiful polyphony takes L’Homme Arme as its cantus firmus, not in spite of the pragmatic decision to reuse a popular pub tune but because of it. It matters that Dante draws on greco-roman literature and cosmology in the Divina Commedia. It matters that Jan van Eyck or Sadao Watanabe recreate biblical stories for their own local contexts, interpreting Christ in both Belgian renaissance- and mid-century Japanese mingei-style clothing and looks. On the flip side, it matters too that “secular” art draws on “Christian” themes: that Marc Chagall uses the crucifixion to comment on the holocaust, that Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem riffs on the requiem mass format, that Beyoncé references the pieta in a music video, or that Andrew Nemr (below) takes inspiration from St. John of the Cross’s “dark night of the soul” for his modern tap dance.

These are but a handful of many examples. But rather than warring over the ownership of artistic meaning (both authorial and audience-received), Culture Care is willing to allow for nuance and complexity in our fast-paced world. It recognizes that there are few, if any, enduring works of art or cultural heritage that do not come to us without complicated interpretative histories. And if we can slow down long enough to listen and behold, I wonder whether we might conclude it is precisely those complications which give these works such enduring depth.

That’s what medieval monasteries were doing, when scribes copied manuscripts of Greek, Roman, and Arabic philosophers and scientists, preserving valuable texts regardless of their religious outlook. The monks had this ability to behold, to wonder, to practice Culture Care. So too did the musicians behind both plainchant and polyphony: the fact that we even have Gregorian chant today is not because it was unique compared to secular styles of the time, but simply because church musicians wrote it down, inventing musical notation to teach these tunes in an age of oral transmission.

Mako calls us back to a sense of wonder in his reflection this month as he considers the tree swallows on his farm in Princeton. Such wonder can only come from a place of humility. To wonder is to remove oneself from the center of one’s own universe, heeding the call of Hamlet that “there are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” This quiet faithfulness to wonder, to stewarding the gifts of generations past while also creating new works of complicated, irreducible beauty — this is the essence of Culture Care.

Jacob Beaird, Editor

A Note from Makoto Fujimura, Founder of IAMCultureCare

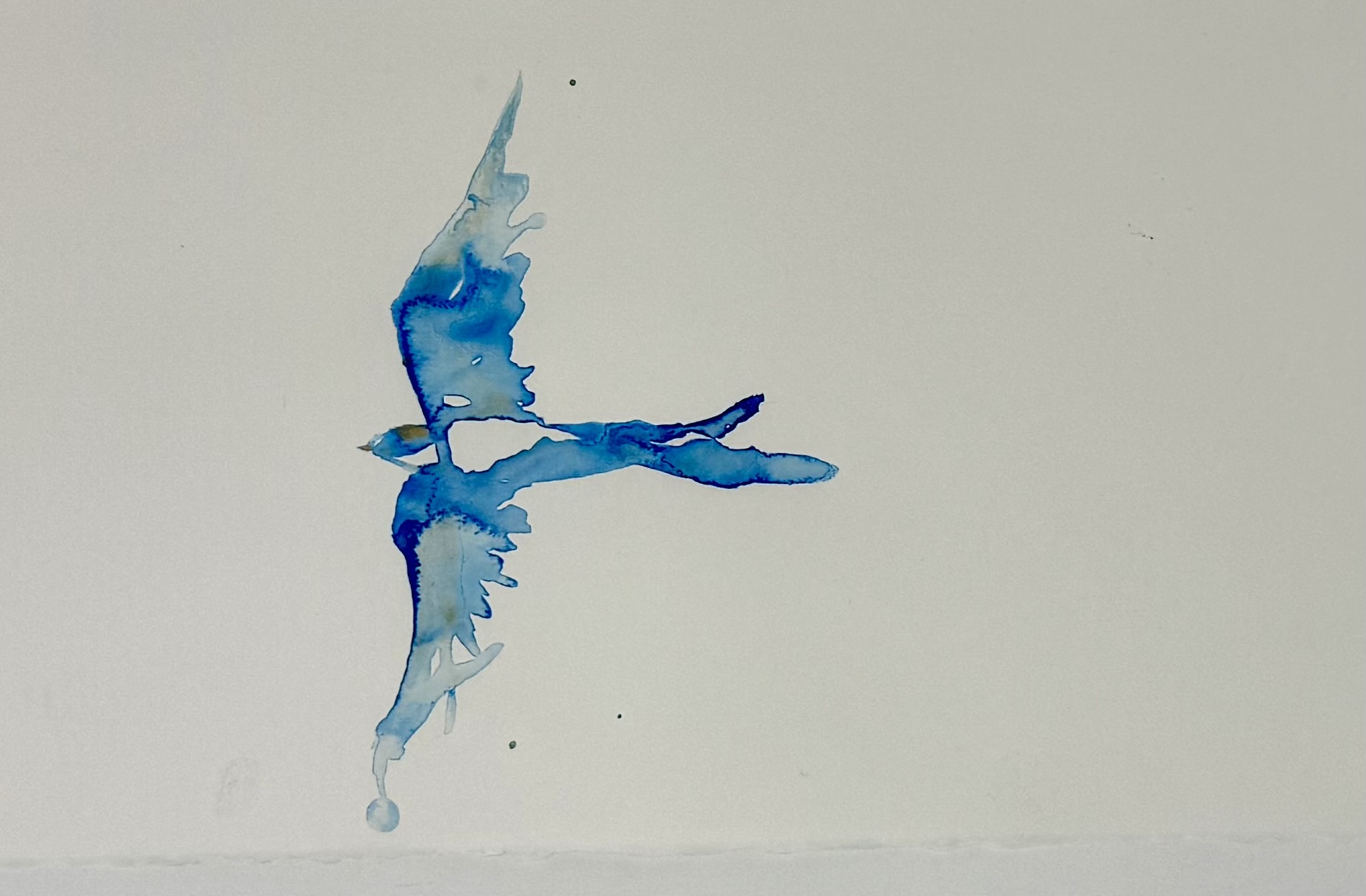

Tree Swallow, 2025, ink drawing. © 2025 Makoto Fujimura.

While checking on my blueberry bushes this morning, I noticed a fledgling tree swallow coming out of the nest, and soon two other little ones followed. It was an amazing privilege to witness their first flight into the world, arcing the heavy, moist June air, and finding their wings’ design.

There is a kind of quiet liturgy in such moments, when the ordinary and the transcendent touch. I stood still in wonder in front of them — they were not startled by my presence (perhaps they had not yet learned to be afraid) — and in that stillness, the garden suddenly became a sanctuary. The growing berries hugged tightly into the curled branches like small eyes of witnesses, and the birds moved through the thick air as if parting a veil. There was no trumpet, no proclamation, just the silent unfolding of what had always been written into their bodies: flight.

I am reminded how creation does not hurry, and yet nothing is left undone. These young birds did not rush into the air — they teetered, they hesitated, they breathed in the wet morning — and then, by some holy consent, they trusted the invisible wind.

Culture Care begins here, too. In the hidden places where trust forms in the faith of ancestral paths, dark and unknown, where beauty incubates quietly in the shadows, waiting for the light to call it forth. Like those fledglings, we are often not certain if we are ready. But the world aches for what we carry. It is not perfection that is demanded, but rather only our attentive presence to the miracle of the first flight, an incarnation of delight.

As artists, as makers, as cultivators of beauty, we are entrusted with the work of patient tending. The soil of our time feels eroded by anxiety and speed, but even so — perhaps especially so — our calling is to plant, to listen, to watch for signs of the invisible becoming visible.

Maybe this is the truest vocation: to become like the swallow, called not by ambition but by an inner call and already embedded design, to participate in the sacred rhythm of becoming.

Let us keep making, even in the overcast hours. Let us continue tending, trusting that something good is always being born just beneath the surface.

* * *

Recently, I had the honor of sharing some like reflections at the Gordon College Commencement on the generational blessings we have inherited. It was a moment to speak into the hearts of young artists, scientists, pastors, and builders of the next culture — to call them to slow down, to listen, to begin their flight not with fear, but with wonder.

You can access the full speech here.

May it encourage your journey, as it did me to see so many wings poised at the edge of the nest, waiting for the wind.

* * *

These Fuji Farm swallows — so small, so seemingly fragile, but already handsomely dressed in their iridescent green coats — will soon journey far beyond these blueberry hedges. By late summer, their wings, now testing the weight of the air above Princeton, will carry them thousands of miles south, over fields and forests, across the Gulf of Mexico, and into the warmth of Central and South America.

They travel not with maps, but with memory — ancestral memory inscribed into the magnetic compass of their cells, navigating by sun and star, temperature and scent, the subtle cues of a world still intact in their bodies. Their return each spring, to me, is a small resurrection; their departure will be a benediction whispered to the wind.

This too is Culture Care: to remember the long arcs of migration, to honor the embedded wisdom that guides both birds and people through seasons of vulnerability and becoming. Just as the swallows leave and return in cycles that predate our calendars, so too we are called to rhythms larger than any one moment — called not only to survive, but to carry beauty across borders and time.

May we live and make with such faithfulness.

May our work remember the wind.

Yours for Culture Care,

Mako Fujimura

* * *

Reflective Questions for Culture Care Groups:

As you consider the fledgling flight of the tree swallows — and your own creative journey — may these questions serve as invitations into deeper reflection, individually or in community:

- What moments in your recent days have felt like “first flights”?

Where have you hesitated, breathed deeply, and trusted the invisible? - Where do you see signs of the “invisible becoming visible” in your own work or in your community?

How might you tend to these signs with greater attentiveness? - The swallows journey by embedded memory and ancestral wisdom.

What generational blessings or embedded wisdom are you carrying forward? What do you long to pass down? - What would it look like for your creative practice to follow natural rhythms — seasons of incubation, flight, migration, and return?

What season are you in right now? - How can we, as artists and cultivators of culture, live in such a way that our lives and work offer “benedictions whispered to the wind”?

Who or what in your life needs a gentle benediction today?

Take your time with these. Read them aloud together. Write. Walk. Let the questions do their slow work. Culture Care begins, and continues, in such small, attentive acts.

Andrew Nemr: Dark Night of the Soul

Photograph by Jerry LaCay, courtesy of Andrew Nemr.

I remember the first time I was frustrated with what I was making. I was in the process of growing from a tap dance performer and choreographer into an artistic director. I wasn’t making routines or pieces anymore (although practically, I was doing that more than ever). What I was really making was a tap dance company — and I wasn’t happy. The distance between my dream and my reality was immense. My relationships were straining under the pressure as the demands I was faced with were growing. Then the financial crisis of 2008 hit. My entire world was rocked. There was loss and grief both personally and professionally. Entire ways of relating and working were lost in the wake of that event. Many things survived, but they weren’t the same.

It was an experience of what some would call a dark night of the soul. While the term was originally coined by St. John of the Cross in the 1500s, many definitions have emerged since. I have come to think about the dark night of the soul as that experience in which the things we use to orient ourselves to the world are stripped away, often without warning or preparation. The financial crisis of 2008 was disorienting, disillusioning, and filled with grief. There have been other such events for me, and I’m sure for many of us. We become different kinds of persons on account of each event.

In recent years I have found my work shifting again to focus specifically on exploring the realities of the spiritual life. Just last fall a few things came together that have invited me into my first new creative work in seven years—Dark Night, an immersive experience designed to bring the idea of the dark night of the soul to life.

Dark Night centers around a 12-hour solo improvised tap dance with direction by Tony Yazbeck and immersive projections by Stephen Proctor. Visitors in-person and online will walk freely through the space, experiencing the dancing and visuals, and interacting with prompts for reflection — namely around the choice to endure.

Dark Night is less performance and more conversation. I am dancing to create a space for, and be a partner in, that conversation. In a culture steeped in instantaneousness, Dark Night seeks to give pause, direct attention to the choice to endure, the spirit within us that enlivens that choice, and the fruit of love that may be birthed from it.

Andrew Nemr is an international artist, teacher, and speaker whose work has crossed music, dance, theatre, film, and the visual arts, exploring art as a vehicle for storytelling and community building. He is a longtime collaborator with Makoto Fujimura and IAMCultureCare. You can listen to Andrew tell the story behind Dark Night here or in this podcast interview.

Culture Care Events & Announcements

- STAY TUNED: Gordon College Exhibition—Boston, MA, August 27-October 15. Mako Fujimura and Bruce Herman to exhibit their original works from the QU4RTETS project alongside newer works by Fujimura in a special exhibit in Gordon’s Barrington Center for the Arts. Additional details and events TBA.

- Makoto Fujimura: Art Is: A Journey Into the Light is published October 21. Mako’s next book with Yale University Press will be available this fall wherever books are sold (pre-order now from any of the retailers linked here!). Art Is takes readers along on Mako’s meandering journey as an artist. We witness him making his“process-driven slow art” — using pulverized minerals, gold, or pigments made from oyster shell — as he considers the plants and wildlife on the land where he lives, including further reflections on tree swallows! Bringing together the author’s written reflections with over 70 of his paintings, drawings, and photographs in full color, Art Is invites us to see the world in prismatic and diverse lights, helping us navigate the fractured, divisive times we live in.

Do you have a news item or upcoming culture care event? Consider sharing it with us for a possible feature here in the newsletter! Email jacob@internationalartsmovement.org.

Web Links

- Mako Fujimura on the legacy of Frederick Buechner, from The Buechner Review.

- Latest Belonging Conversation from Mako Fujimura and Julia Hendrickson.

- From the archives: Mako Fujimura on the art of Toshiko Takaezu.

- Mary Alvarado’s beautiful reflection on shape note singing, AI, and what it means to be human, in Image Journal

- Ben Christenson for Inkwell on creating human spaces in a dehumanizing culture.

- Also for Inkwell, poet Scott Cairns considers Annie Dillard, poetry, and conversing with the dead.

- New music recs: Jazz banjo, drums, and harp? Béla Fleck and friends make it work; an eclectic album from the internet’s favorite organist, Anna Lapwood; viol consort Fretwork plays music of Orlando Gibbons, 400 years dead this year.

- Image interviews architect Rick Archer on Ellsworth Kelly’s final building, “Austin”.

- A 1920 map of fairy tales and mythologies.

- Poignant (but paywalled), an Economist obituary pays tribute to Martin Graham, who built an opera house out of his chicken coop in the English countryside.

IAMCultureCare is a registered 501c(3) non-profit organization that relies on your support to continue our Culture Care efforts of amending the soil of culture as an antidote to toxic culture wars. This newsletter and our other programming do that effectively, and we welcome gifts of any size to continue these efforts. You can donate online or get in touch with us about corporate sponsorship and other giving methods!

All content in this newsletter belongs to the respective creators, as noted, and is used with permission. If you would like to submit something for consideration in a future newsletter issue, you may do so by filling out this form or by emailing jacob@internationalartsmovement.org.