Contributors: Makoto Fujimura, Eva Crawford & David Grossman

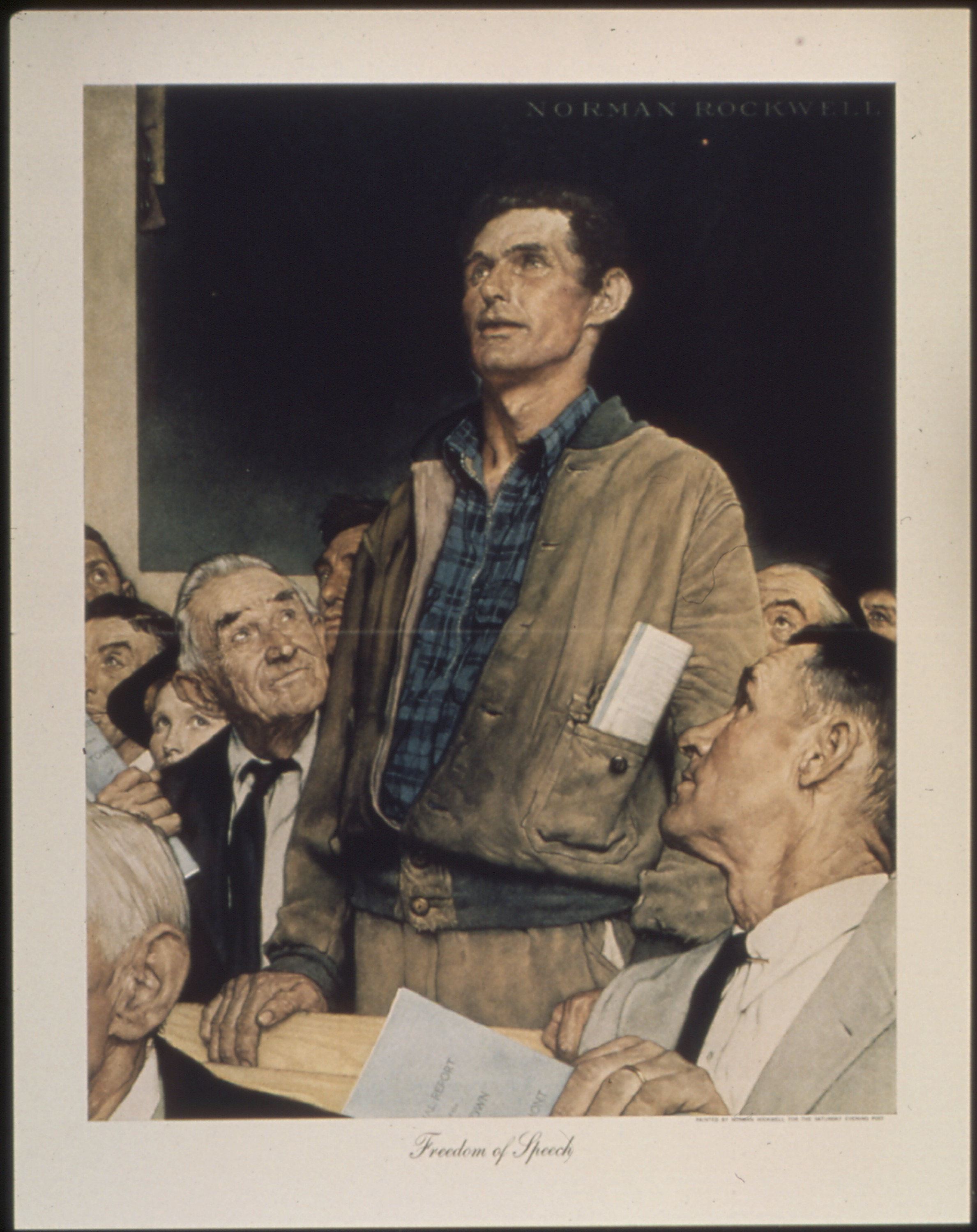

Heading Image: Norman Rockwell, Freedom of Speech, from “The Four Freedoms”, 1943. Oil on Canvas. 45.75 in × 35.5 in. Stockbridge, MA, Norman Rockwell Museum. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons and the National Archives and Records Administration NAID 513536, accessed June 10, 2024.

A Note from IAMCultureCare

In this June, 2024 issue of the Culture Care Newsletter, we highlight three artists: one historical, and two members of our Culture Care community.

Makoto Fujimura’s regular column reflects on the life and work of Norman Rockwell, 20th-century American illustrator of common life, whose art depicted not only the spirit or sentiment(ality) of America, but also prophetically envisioned what America could be through the lives of regular people. Mako can tell it better than I can, so be sure to read his reflection below.

Next, we feature a 100-day collage project by Eva Crawford based on the famous “Love” chapter from 1 Corinthians. The found photographs she uses in her collage are relics from a similar era as Rockwell’s illustrations, but they are extracted, literally cut out from their context. Paired with a single word or phrase, they dialogue with one another to breathe fresh meanings into a familiar text and historical period. To borrow language from Mako’s piece below, it “jolts” us out of complacency, forcing us to reinterpret both the words and our own preconceptions of the past the images allude to, for our own present moment. Regretfully, this newsletter platform limits a higher resolution image of the entire series, so after reading Eva’s reflection in this newsletter, I encourage you to slowly peruse the individual collages on her Instagram, linked below.

We also feature art by David Grossman and his reflection on time and gratitude and how they intersect within his work. The word “gratitude” is etymologically related to “grace”, and there is a sense in which gratitude is a wholehearted assent to living in a gift economy. It is a recognition that the circumstances of ordinary life (regardless of one’s faith identity) are mysteriously given to us, and to accept them as such is also to accept a duty to respond in kind. David’s art is such an assent and response. And, in turn, it is in invitation to the viewer to enter into that gift-gratitude cycle that defies limits of scarcity. The natural world depicted in the landscapes seems alive not (merely) in a sense of verisimilitude but in its ability to leap at once into the imagination and take on a life of its own; I can “see” the birds in flying off the edge of the frame, the currents of the air, the brief moment of a sunset slipping beyond the horizon, and yet there is also a stillness that lingers. Time here is internal and fluid rather than external and linear.

In each of these examples, the extraordinary whole is more than the sum of its ordinary parts: Norman Rockwell’s Americana, Eva Crawford’s old magazine photos collaged with a familiar text, David Grossman’s landscapes created in the midst of the quiet panic of parenthood — they all speak beyond those contexts even as they directly depict them. They are gifted responses to a gift economy of abundance rather than scarcity. Or, to borrow Jared Stacy’s framework in recent newsletter issues, each of these are depictions of chronos time that live on in kairos revelations. Or, to borrow philosopher and friend of IAMCC Esther Lightcap Meek’s framework, these are responses to the invitations of the Real. Culture Care is to make into that invitation.

Jacob Beaird, Editor

A Note from Makoto Fujimura, Founder of IAMCultureCare

When I was majoring in art at Bucknell University, I remember reading several scathing critical reviews of Norman Rockwell by contemporary art critics. It was the heyday of transgressive art and minimalism, and Rockwell was seen only as a sentimental illustrator of Americana. Some even argued his art was not really “art”, as it did not create a new way to see art. Anything akin to “mall art” was labeled as a “sell out” in the commercial realms. Perhaps it is still seen that way in some circles.

But seeing Rockwell’s actual paintings recently at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA, confirmed what I suspected for many years. Even as a student, I had to learn to see beyond these critics. Norman Rockwell, like Winslow Homer and Edward Hopper, transcended his successful illustration career. These artists were the illuminators of our history, visual prophets painting what America longed to be. They all turned out to be fine, enduring and innovative artists, that honored the past and redefined their medium, providing a generative vista for the next generations of artists. Today, art schools should examine their indelible heritage, and reintroduce drawing classes to their curriculums rather than discarding them for digital media. They need to see (and learn from) the great illustrators of our time as artists, such as my friend Jerry Pinkney (who sadly passed away during the Covid shutdown, but whose work also graces the walls of the Norman Rockwell Museum) and our friend John Hendrix.

Take Rockwell’s Freedom of Speech painting that is part of his “Four Freedoms” series as an example, inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union address. The series aimed to visualize the four essential human freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. Two years later, Rockwell completed all four paintings on these themes.

Freedom of Speech stands out to me among other iconic “Freedom” works of Rockwell. This is a portrait of a citizen neighbor, Jim Edgerton, rather than Rockwell’s typical subjects of historical figures or iconic scenes (such as the famous Thanksgiving meal painting, the Freedom from Want of the “Four Freedoms” series). Rockwell personally witnessed the moment Edgerton stood up to speak as the lone dissenter to his town‘s plans to build a new school, as the old one had burned down. Edgerton was given the floor as a matter of protocol, and he expressed concern about the tax burden of the proposal, as his family farm had been ravaged by disease. To Rockwell, this was not just a fulfillment of a protocol: this was as a slice of a picture of America, and Rockwell immediately sought to capture this moment. But, he ended up wrestling with this image for several months, eventually abandoning the first painting (he is quoted as saying he “overworked it”, which shows his passion for this project), and two others, before starting afresh on the painting now on display. According to Bruce Cole (former chair of the National Endowment for Humanities, that I got to know personally), Edgerton is shown “standing tall, his mouth open, his shining eyes transfixed, he speaks his mind, untrammeled and unafraid”, and his face and figure resembles Rockwell’s Abraham Lincoln as a young lawyer defending an unjustly accused defendant in the famed “Almanac case” that propelled Lincoln’s legend.

Like the later young Lincoln portrait, Edgerton’s lanky figure imposes a dramatic movement, breaking the visual plane, and we are jolted to look up at him. The smoothed surface and the lack of painterly gestures create a psychological “coolness” of the surface, drawing our eyes straight into the face of the speaker. It’s been noted that such restraint in painterly expression is due to the illustrative purpose (to be on the cover of Saturday Evening Post). This made sure that the image communicated well in both photographic and print translation. Perhaps so (other paintings, even in the same series, use different painting layering technique), but looking at the actual painting made me appreciate how much subtle movement Rockwell captures, particularly in Edgerton’s face: a stoic resistance against a dark background, isolated, simple but nuanced. It is no coincidence that the young Lincoln portrait parallels Freedom of Speech. This face captures a man with the conviction to exercise his right as a citizen, even though he is a novice, not sure of his own ability to do so. Rockwell intuited that democracy is built on such a moment. It is the same moment we see in a “jury of peers” standing up to make a fair judgment against a powerful man, despite the enormous pressure to succumb to fears and the media mob.

Art can capture the sacred in every person, injecting nobility in the ordinary. Rockwell painted not just the surfeit sentiment of America, as the critics so readily claimed, but her deep longings; not just the sentiment of the ordinary, but the impossibilities of the ordinary colliding with history’s extraordinary moments. Culture Care is to see art as a portal into such sacred moments, a stewardship of gifts that reveal our time, our hopes. This trained intuition forms diverse tributaries, that one can see in Rockwell’s paintings (even in a single painting, in this case), and such powerful confluences come together in a generative gift to be appreciated in person many years later.

Mako Fujimura

Art Feature: Eva Crawford

Love, collage of found photos and up-cycled paper on 2”x3” handmade paper from India. Copyright © 2024 Eva Crawford.

The daily investigation of each small segment fostered a micro level of contemplation and meditation. The “love” chapter is heard frequently, yet is relevant for today’s culture care as the mending and relationship building can only happen by abiding by these words.

“All the Loves” detail from Love, collage of found photos and up-cycled paper on 2”x3” handmade paper from India. Copyright © 2024 Eva Crawford.

100 days of dedication to making is a global art project as seen on Instagram @dothe100dayproject. Each February of the last four years I experienced a dread/excitement as I faced the slow art of completing this disciplined endeavor. Years one and two I illustrated poems written by my son and my father. Last year I completed an interpretation of the Psalms. This year was a tribute to love as I focused on portraying 1 Corinthians 13 by creating a daily collage using old found photos and up-cycled paper on a stack of 2”x3” handmade paper from India.

I posted each word or small phrase composition of the day as #100dayproject1Corinthians13 until 100 days later the chapter segment was complete. As in previous years, the daily investigation of each small segment fostered a deep micro level of contemplation and meditation. The “love” chapter is heard frequently in weddings and sermons, yet is relevant for today’s Culture Care, as mending and relationship building can only happen by abiding by these words:

“If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. And if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but have not love, I am nothing. If I give away all I have, and if I deliver up my body to be burned, but have not love, I gain nothing. Love is patient and kind; love does not envy or boast; it is not arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice at wrongdoing, but rejoices with the truth. Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. Love never ends.

…So now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love.”

1 Corinthians 13:1 – 8a, 13

Eva Crawford is a full-time Charlotte, NC artist painting, drawing, and collaging beautiful vessels of the human soul. Her work ranges from expressive to intricately slow artworks which reflect the necessary time required to know another human and to gain deeper understanding. Her work can be seen on Instagram @evacrawfordart or www.evacrawfordart.com.

Art Feature: David Grossman

Currents, 30″ x 40″ Oil on Linen Panel. Copyright © 2024 David Grossman.

Resting Place, 30″ x 50″ Oil on Linen Panel. Copyright © David Grossman.

Winter Neighbours, 20″ x 34″ Oil on Linen Panel. Copyright © 2024 David Grossman.

Gifts

When I began working on these paintings two years ago, I felt an undercurrent of panic. Would I have enough time to finish? Enough energy? My son had just been born and the joyful upheaval of becoming a parent left me staggering to find a new balance.

As a parent, time seems to speed by much faster than it did before. The days are a blur of trying to keep up with the energy and imagination of a toddler. The nights are often interrupted by his crying, and as I hold my son and settle him back to sleep I marvel at how fast he is growing.

Life gradually settles into new rhythms, and I feel a deeper sense of gratitude taking shape in the wake of my receding panic. Along the way my son turns two and I turn forty. My paintings begin to reflect this season of compressed time and of broadening gratitude, more than ever blurring the lines between the world and my inner landscape of thought and emotion.

And so when flowers bloom in my garden they also emerge as symbols of impermanence and hope, of my vulnerability and of the fragility of a world at war. Migrations of birds become meditations on my own journeys in and out of the unknown. Lights from our neighbour’s windows bring to mind the isolation and connection of our day to day experience. The cat and birds that frequent my yard remind me of the commonplace dramas, often of survival, that run parallel with my daily routines. Patterns on the surface of water turn into musings on aging and memory. All of these circle back in their ways to themes of time and of gratitude, to the reminders that what I am given day by day is, after all, enough.

David Grossmann explores the space between nature and the inner landscape of perception and contemplation, intuition and memory. His paintings take shape in a slow progression that allows each to become a meditative, reverent space. His work can be seen at his website and in this short film. His upcoming solo show “Gifts: exploring time and gratitude through landscapes” runs June 19-July 20, in London, UK.

Culture Care Events

- Mysterion Makoto Fujimura Exhibit at The Galleries at First Pres — Greenville, SC, Now —July 25. Mini-retrospective of Makoto Fujimura’s works.

- Painters, Prophets, Poets Conference — Oklahoma City, OK, Oct 4 – 6. Makoto & Haejin Fujimura will speak alongside Beth Moore, Malcolm Guite & Miroslav Volf on creativity, imagination, culture, and New Creation.

Do you have a news item or upcoming culture care event? Consider sharing it with us for a possible feature here in the newsletter! Email jacob@internationalartsmovement.org.

Web Links

- IAMCC board member Bruce Herman on magic and grace, in Mockingbird: “Mystery and play are not attempting to undermine truth or reality; rather, they are encouraging us to hold our certainties with a bit more humility.”

- Latest Belonging Conversation from Makoto Fujimura and Julia Hendrickson.

- Computers can’t do math, argues David Schaengold in a long read from Plough on AI, the limits of metaphor, the nature of intelligence, and what it means to be human.

- Matthew Milliner interviews architect Amanda Iglesias on “The Architecture of Prayer”.

- Julia Cho in the New York Times, on conferences as a place for rejuvenation. She highlights Makoto Fujimura’s live painting collaboration with pianist Yukari Soma and tea master Keiko Yanaka, as well as an IAM conference with poet Christian Wiman.

- Brief clip of Makoto Fujimura interviewing philosopher Gordon Graham, on Culture Care and the Scottish Enlightenment.

- The Smithsonian’s Ode to Cicadas.

- New music recs, from: Caroline Shaw & Sō Percussion (alternative classical, out on June 14 from Nonesuch), The Sixteen (eclectic choral tribute to conductor Harry Christophers), The Infamous Stringdusters (bluegrass/folk, music inspired by rivers).

All content in this newsletter belongs to the respective creators, as noted, and is used with permission. If you would like to submit something for consideration in a future newsletter issue, you may do so by filling out this form or by emailing jacob@internationalartsmovement.org.