Contributors: Makoto Fujimura, Hannah Rose Thomas & Jared Stacy

Heading Image: Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn). Bust of an Old Bearded Man Looking Down, Three-Quarters Right. Etching; third state of three. 1631. Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/391518 (accessed February 13, 2024). Public Domain.

A Note from IAMCultureCare

Dear newsletter readers,

Today begins the ancient season of Lent for the Christian church, a time of self-reflection and intentional practices of fasting, prayer, and generosity. All three are meant to be reminders of our common spiritual poverty in a world that ever seeks to be satisfied. Yet as you will shortly read and see, this poverty is not the final answer. Our newsletter this month reflects on how beholding, or attention, or receptivity (all these words are getting at the same thing), actually allows for abundance in the midst of apparent scarcity. IAMCultureCare founder Makoto Fujimura’s regular column features a brief update on his ongoing exhibits via a reflection on beholding. Then, we feature stunning portraits by British artist Hannah Rose Thomas in a special preview of her forthcoming book Tears of Gold,highlighting stories of women who are survivors of violence in the Global South. We then close this February issue with the second installment of theologian Jared Stacy’s essay series, An Ethos of Culture Care: Material.

Our heading image is an etching by the 17th-century Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn. Rembrandt’s work is remarkable for many reasons (not least the way his paintings capture light so effortlessly). As a portrait artist he was in high demand by the wealthy elite, and yet unusually for his time he frequently took the poor, ordinary, ignored people around him as subjects for his art. It is these works that I think are some of his most enduring and transcendent. As you ponder the pieces in this February newsletter, consider the overlooked moments and people in your lives where you might begin to behold, to pay attention, to receive — and therefore create space for grace.

Feel free to get in touch with us at IAMCultureCare or with any of our featured creators; we’d love to keep the conversation going. And as always, continue to reach out with news items, art, essay, or anything else that we might share in this newsletter. Simply reply to this email for further information or complete this Google form when it goes live later this month. This is your space for your Culture Care stories.

Jacob Beaird, Editor

A Note from Makoto Fujimura, founder of IAMCultureCare

Dear Culture Care Communities,

My Weisman Museum exhibit opened in January, and Haejin and I were delighted to be at the beautiful Pepperdine University campus to lecture on Beauty+Justice and be at the opening. At the opening and the lecture I met many people for the first time. As we prepare for our event at The Galleries at First Pres on March 1st (find more details below in the Culture Care Events section), we look forward to meeting many more!

Several poignant conversations stood out to me. One couple shared about how my Art+Faith: A Theology of Making led to their recovery of faith. Many took the advice of the exhibit’s wonderful curator, Andrea Gyorody, to behold each painting for at least ten minutes. Even at the opening event, we saw many doing that, reporting that they were astonished at what they could see after they spent some time beholding.

Art provides a needed respite for our overactive brains and allows us to pause our judgmental, knee-jerk responses we cultivated for our survival. Culture Care is a movement of beholding, pausing to see, hear, and taste the goodness and beauty all around us (or to create anew in the midst of scarcity — be sure to read Jared Stacy’s piece on this below). May your lives reflect such acts of beholding and the experience of being held by Grace.

Makoto Fujimura

Photo by Ron Hall of the exhibit opening to “Makoto Fujimura: Water Flames”, posted by the Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art, January 25 on Instagram @weismanmuseumofart.

Book Preview: Tears of Gold

By Hannah Rose Thomas

It has been an honour to speak at the International Religious Freedom (IRF) Summit in Washington DC, about my portrait paintings of survivors of religious and gender-based persecution.

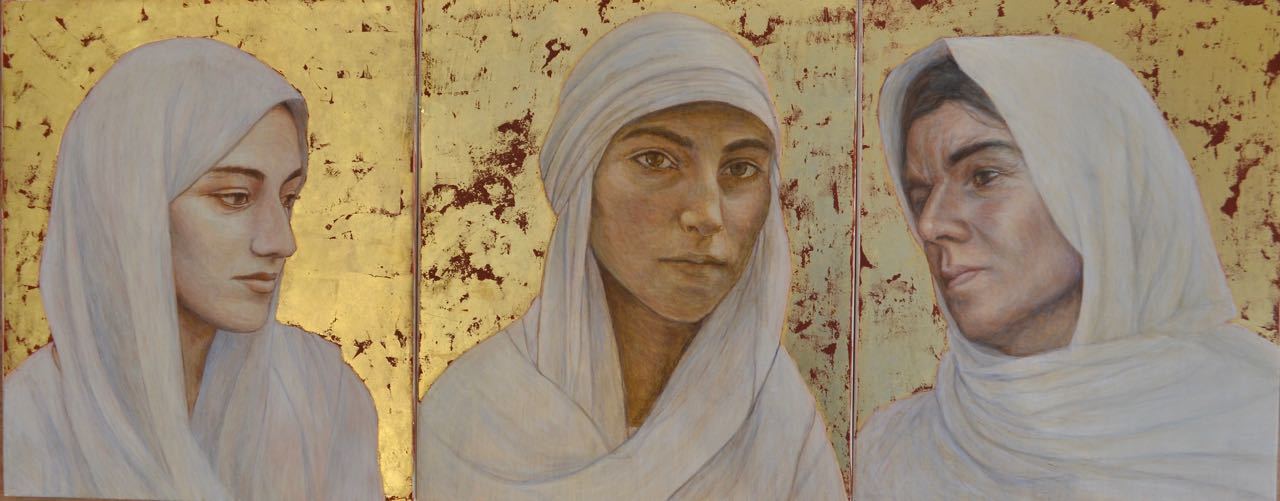

Tears of Gold collects my portrait paintings of Yazidi women who escaped ISIS captivity, Rohingya women who fled violence in Myanmar and Nigerian women who survived sexual violence at the hands of Boko Haram and Fulani militants. My most recent portrait is of an Uyghur survivor of the concentration camps in Xinjiang, China. I had the privilege of encountering many of these women during my time organising art projects in Iraqi, Kurdish & Bangladeshi refugee camps and Northern Nigeria.

As women from religious minorities, they had suffered persecution, forced displacement, and many had been subjected to sexual violence. Due to the stigma surrounding such violence they faced shame and isolation within their communities. All too often their stories remain unseen and unheard.

After learning to draw and paint for the very first time, the women also asked whether I would paint their portraits. It felt a privilege to be trusted to share their stories in this way.

For their portrait paintings I used religious symbolism and gold leaf to convey the sacred value of each and every individual regardless of gender, race or religion. ‘Sacred’ is derived from the Latin sacrare meaning ‘to make sacred, consecrate; set apart, dedicate.’ Former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams affirms that “without art we should not fully see what sanctity is about” (“God and the Artist,” in Grace and Necessity: Reflections on Art and Love).

The gold leaf is reminiscent of icon paintings. The purpose of icons are to support prayer and contemplation. These portraits, painted with the painstaking egg tempera technique, offer an invitation to pause, to hesitate before such inexplicable suffering. This aligns with a theological account of lament, which places human suffering before God’s compassionate witness and tender care. It is my prayer that God would open my eyes to see each person as He sees them, to reverently behold the imago Dei, especially in the places where it has been denied.

The painting process itself could be perceived as an expression of French Philosopher Simone Weil’s concept of Attention: This “attention,” she writes, “taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer” (Gravity and Grace). This reverent attentive beholding is at the heart of my practice of portrait painting. In Iris Murdoch’s summation, attention is “a just and loving gaze directed at an individual reality” (“The Idea of Perfection,” in The Sovereignty of Good). The type of attention Weil aligns with love: “the name of this intense, pure, disinterested, gratuitous, generous attention is love.”

According to Weil, what individuals who have experienced grave suffering most need is “people capable of giving them their attention.” To put it simply, Weil’s attention is recognition. Weil writes: “The capacity to give one’s attention to a sufferer is a very rare and difficult thing; it is almost a miracle; it is a miracle … [this] restores to the living thing his or her humanity” (Waiting for God). There is nothing more valuable we can give to another than the full recognition of his or her humanity. I believe that the arts can help to bring healing and restoration; and can create a space of hospitality to attend and to bear witness to one another. I have come to perceive portrait painting as a gift of attention, a way for individuals to feel seen and heard, that they may have never experienced before.

Attention is also profoundly realized in our encounter with works of art, perhaps surpassed only by our encounter with another person, or what the Philosopher Emmanuel Levinas calls the Infinite in “the face of the other.” These portraits have been displayed in places of influence in the Global North to enable the women’s voices to be heard and to advocate on their behalf. It is my hope that Tears of Gold will help to bring attention to and elevate the dignity of women from some of the most vulnerable and marginalised communities around the world. And that it will offer a gentle reminder of the inherent dignity and sacred value of each and every individual in the eyes of God.

Excerpts from Tears of Gold: Portraits of Yazidi, Royhinga, and Nigerian Women, from Plough Publishing House, 2024.

Portraits of Yazidi Women, Tempera and 24ct Gold Leaf on Panel, 2017, 10″ x 8″ each panel. Copyright © 2017 Hannah Rose Thomas.

Portraits of Nigerian Women, Tempera and 24ct Gold Leaf on Panel, 2018, 14″ x 12″ each panel. Copyright © 2018 Hannah Rose Thomas.

Hannah Rose Thomas is an award-winning British artist and human rights activist. Her new book Tears of Gold: Portraits of Yazidi, Royhinga, and Nigerian Women is available for purchase. To see more of her work, check out Hannah’s website or Instagram, or attend the book launch & exhibit in London on March 8.

Essay Feature: An Ethos of Culture Care (Material)

By Jared Stacy

This month, we turn from the time of culture care (the kairic moment of now) to the material of culture care. Last month, we saw that time matters for an ethic of culture care. Recall there is the chronos of quantitative time: years, months, seconds, and the kairos of qualitative time: opportunity and possibility, the right moment. And if culture care is attuned to kairic possibility, we now turn to ask, what material is made available to us in this kairic moment?

An ethic of culture care seizes the kairic now — even a moment filled with ruin and reckoning — as the moment where God’s grace provides the material for the new. The task of a culture care ethic in a fragmenting world is thus to cultivate a transformative receptivity to the material of new creation. In contrast, an ethos of culture war demands not receptivity but militancy that reduces human beings to raw material. Culture war militancy always assumes scarcity, and thus only ever promotes a combustible, fragile order based on domination of the other.

But the ethos of culture care that we are presenting here is different. It proceeds not from scarcity, but from a belief in a divine economy of abundance. And not just any abundance: the task of an ethic of culture care is to cultivate receptivity to God’s generous abundance permeating our present — receptivity to grace and the dimension of new creation.

The material of culture care, then, is grace. But not just abstracted or idealized. Rather, it is the very embodied life of Jesus Christ, the bread and the cup, the waters of baptism. An ethic of culture care cultivates receptivity to this grace as that which overcomes the world.

But this overcoming is not retribution — but reconciliation and resurrection. Receiving this grace of God in Jesus Christ trains us to “renew our minds” (Romans 12:1 – 2), and in this renewal we become receptors to God’s way of working in a world he refuses to abandon to itself.

This can happen in the worst of times, in the ruins of all that was once hoped for. In the winter of 1940, across Nazi-occupied Europe, Dutch pastor-theologian K.H. Miskotte witnessed something incredible: new Bible studies. They were not like the pre-War gatherings of pious, middle-class, spiritual meetings that ran parallel to “real life.” They were gatherings in the real of the kairic now. They met in a crucible where the material of lived desperation and a desire to resist received God’s generous abundance of new creation. Pockets of Christians and non-Christians alike began to open and read the Bible in a moment when Europe’s greatest cities were covered by the shadow of encroaching tyranny and authoritarianism. Imagine: people of all walks of life, suddenly (and quite against their will) brought to a place of humble hope, lament, and (in this) finding a new receptivity to God’s grace in the ruins.

This culture care receptivity to grace will often be met by collaborators, sympathizers, and purveyors of culture war and its militancy. The tyranny of chronos, of the scarcity of time and material, binds human beings as captives to fate, rival words, and false ways of being. And yet, the receptivity to grace that an ethic of culture care provides often fuels a new resistance, a new hope in the lives of human beings who find themselves capable of resisting the fatalism and false necessities that assault us from the worlds our words have created. This is a scandalous act of witness to a world which sees no other way forward but to become collaborators and sympathisers with “the way things are.” The militancy of culture war is our creation, but the receptivity of culture care turns us to receive the new creation of Jesus Christ.

Next month, we conclude with the presence of culture care. Because this receptivity requires presence in the kairic moment of now, there is also risk involved as receptivity in a world of militancy will always be swiftly punished. Yet this receptivity is never passive, but rather demonstrative: it crosses borders, forges new social bonds, and witnesses to abundance with even the scantest of material. An ethic of culture care holds that all such action and building is — ultimately — primed by receptivity to the material of new creation.

Jared Stacy is an American ethicist and theologian residing at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland as a PhD candidate. His research focuses on political extremisms and political theology. You can find him on platforms like Substack, Instagram, and X.

Culture Care Events

- “My Bright Abyss: Paintings & Prints” Makoto Fujimura Exhibit at Bradford Gallery — Nashville, TN, Now — March 31. The exhibit is open on Sunday mornings and for special events, as well as group tours. Contact the St. George’s Episcopal Church office to find out how to visit. Rabbit Room founder Andrew Peterson will give a lecture at the exhibit on February 21.

- “Mysterion” Makoto Fujimura Exhibit at The Galleries at First Pres — Greenville, SC, Now — July 25. Mini-retrospective of Makoto Fujimura’s works. Fujimura will be speaking at the Mystery of Beauty Conference held at First Presbyterian Church on March 1, 2024.

- “Water Flames” Makoto Fujimura Exhibit at Pepperdine University’s Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art — Malibu, CA, Now — March 31. This exhibit brings together a number of Fujimura’s major paintings of the last 20 years, focusing on the poetic paradox between the elements of water and fire, which symbolize, in Fujimura’s words, art’s power to “[turn] the flames of destruction into the flames of sanctification.”

- The Overseas Ministries Study Center at Princeton Theological Seminary is accepting applications for their 2024 – 2025 Artist in Residence Program. Check out the OMSC site for more information.

- Farming for the Future — Montgomery, NY, March 9. From Plough: “Joel Salatin and James and Helen Rebanks, prominent advocates of sustainable agriculture from both sides of the Atlantic, discuss the future of farming.” Plus, there’s a barbecue!

- Tuesdays with Morrie — Seadog Theater, NYC, March 1 – 31. This limited run production of a poignant (& culture care) story has a number of IAMCC connections, including Board Member Bruce Shaw’s daughter Sally Shaw, who is company manager at Seadog and is featured as a vocalist. Newsletter readers who attended IAMCC Partner Embers International’s 2022 Virtual Gala may remember Sally’s beautiful musical performance during that event.

Do you have a news item or upcoming culture care event? Consider sharing it with us for a possible feature here in the newsletter! Email jacob@internationalartsmovement.org.

Web Links

- January Belonging Conversation between Makoto Fujimura and IAMCC board member Julia Hendrickson.

- A long read from The Guardian on social media algorithms that “flatten” culture.

- Alice Courtright on ballet dancer Thomas Forster and the social dimension of dance, in The Hedgehog Review.

- For the first time since 1803, two cicada broods emerging together this year in the US.

- Poet Christian Wiman just gave an excellent lecture on “The Art of Faith, the Faith of Art”.

- Ben Proudfoot’s beautiful documentary short The Last Repair Shop is Academy Award nominated.

- Makoto Fujimura and Haejin Shim Fujimura on why fighting for justice and creating beauty are really the same thing.

- Composer Caroline Shaw presents a three-part BBC radio program on color in music.

- Why William Blake’s prophetic art is needed now, from Plough Magazine on the occasion of the Getty Center’s recent Blake exhibit.

- Jonathan Rogers on art and the gift economy.

- John Cage’s piece Organ2/ASLSP (or “As Slow As Possible”, the ongoing performance of which is projected to last 639 years), just had a note change for the first time since 2022.

All reader-submitted content in this newsletter belongs to the respective creators, as noted, and is used with permission.